This is particularly the case taking into account that the Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law in 2022, calls for 100% of cars manufactured to be electric vehicles by 2035. But an electric vehicle requires three to five times as much copper as an internal combustion engine vehicle — not to mention the copper required for upgrades to the electric grid.

“A normal Honda Accord needs about 40 pounds of copper. The same battery electric Honda Accord needs almost 200 pounds of copper. Onshore wind turbines require about 10 tons of copper, and in offshore wind turbines, that amount can more than double,” said Adam Simon, co-author of the study. “We show in the paper that the amount of copper needed is essentially impossible for mining companies to produce.”

The shortfall is in part because of the permitting process for mining companies. The average time between discovering a new copper mineral deposit and getting a permit to build a mine is about 20 years.

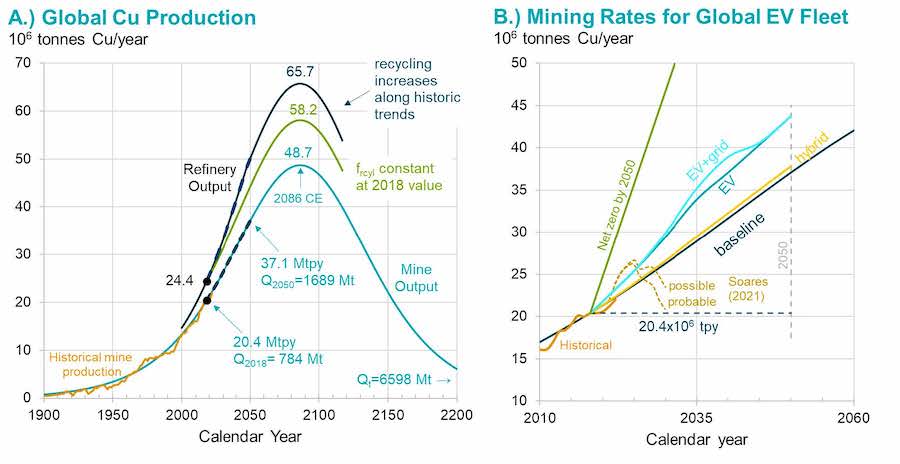

Copper is mined by more than 100 companies operating mines on six continents. The researchers drew data for global copper production back to 1900, which told them the global amount of copper mining companies had produced over 120 years. They then modelled how much copper mining companies are likely to produce for the rest of the century.

What’s achievable

The researchers found that between 2018 and 2050, the world will need to mine 115% more copper than has been mined in all human history until 2018 just to meet “business as usual.” This would meet our current copper needs and support the developing world without considering the green energy transition.

To meet the copper needs of electrifying the global vehicle fleet, as many as six new large copper mines must be brought online annually over the next several decades. About 40% of the production from new mines will be required for electric vehicle-related grid upgrades.

“I’m fully on board with the energy transition. However, it needs to be done in a way that’s achievable,” Simon said.

Instead of fully electrifying the US fleet of vehicles, the researcher suggests focusing on manufacturing hybrid vehicles.

“We are hoping the study gets picked up by policymakers who should consider copper as the limiting factor for the energy transition, and to think about how copper is allocated,” Simon said. “We know, for example, that a Toyota Prius actually has a slightly better impact on climate than a Tesla. Instead of producing 20 million electric vehicles in the United States and globally, 100 million battery electric vehicles each year, would it be more feasible to focus on building 20 million hybrid vehicles?”

The researcher also points out that copper will be needed for developing countries to build infrastructure, such as building an electric grid for the approximately 1 billion people who don’t yet have access to electricity; to provide clean water drinking facilities for the approximately 2 billion people who don’t have access to clean water; and wastewater treatment for the 4 billion people who don’t have access to sanitation facilities.

“Renewable energy technologies, clean water, wastewater, electricity — it cannot exist without copper. So we then end up with tension between how much copper we need to build infrastructure in less developed countries versus how much copper we need for the energy transition,” Simon said.

“Our study highlights that significant progress can be made to reduce emissions in the United States. However, the current — almost singular — emphasis on downstream manufacture of renewable energy technologies cannot be met by upstream mine production of copper and other metals without a complete mindset change about mining among environmental groups and policymakers.”